Source: Boston Globe

By Tim Logan

Massachusetts needs about twice as many apartments that are affordable to low-income renters as it has, according to a study, and the need could grow in coming years.

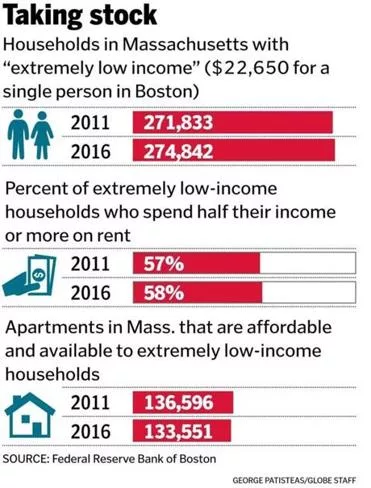

A report released Wednesday by researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston said the state has 274,842 “extremely low-income households” — those earning up to $22,650 for a single person and no more than $29,150 for a family of three — and just 133,551 apartments available at rents they can afford.

Because housing is so precious, most low-income earners have to pay one-third, and often more, of their monthly income on rent.

These households “often have to forgo spending on health care, food, child care or other necessities,” the report said. “A single financial shock — a job loss or a large medical bill — can cause this group to fall behind on rent, leading to eviction or even homelessness.”

The number of low-income renters in the state has grown slightly since 2011 — and not as fast as the population of better-off renters — while the number of apartments they can afford has declined.

Housing pressures could grow worse as government-backed financing for existing affordable housing developments expires. More than 9,000 subsidized apartments in Massachusetts are due to lose their subsidies by 2025, which would leave 25 cities and towns without any subsidized housing at all.

State officials, housing nonprofits, and leaders in some cities such as Boston are trying to tackle this so-called “expiring use” problem by buying or refinancing older affordable housing as those subsidies expire, and keep low-income tenants from being pushed out by higher rents. But, they note, that requires scarce public money that could otherwise be used to develop new affordable housing.

By 2035, the report estimates, it could cost $843 million to $1 billion a year to preserve and develop new affordable housing for low-income renters in Massachusetts.

Some housing advocates are campaigning for measures that could more directly help low-income tenants, such as expanding the state’s rental voucher program.

The Boston Fed study notes that vouchers can be more effective at helping people find affordable housing than federal tax credits that are used to build affordable units. And it raises the possibility of targeting more vouchers for lower-cost parts of the state — such as Central and Western Massachusetts — while using more tax credits to subsidize new affordable housing in Greater Boston, which is more expensive.

Either way, the findings, which echo those in other reports on the region’s deep need for more affordable housing, did not come as a surprise to groups that work on housing for low-income people. But, they said, the study is another wake-up call for Beacon Hill lawmakers as they debate how to tackle the state’s housing shortage.

“Throughout its history, Massachusetts has taken the lead on many initiatives and dedicated state resources to prevent homelessness and support affordable housing,” said Metro Housing Boston, a housing nonprofit that co-hosted a panel talk about the Fed report on Wednesday.

“We should therefore not settle for falling behind on the effort to address this emergency or rely on municipalities to do so voluntarily.”